This is the third part of a multi-part series.

User groups were the lifeblood of any Atari community, bringing together hobbyists to have fun and help each other.

Consider ST-JAUG, the “ST Jacksonville Atari Users Group,” a computer club full of active-duty and retired military in the Jacksonville, Florida, area.

On May 21, 1988, many of them could be found at the heart of an airplane hangar at the Jacksonville Naval Air Station, manning a large booth with more than 20 Atari ST computers on display. The occasion? The eighth annual Armed Forces Day / Scout World event. It was a golden opportunity for the club to “STrut their STuff” for thousands of Boy Scouts and their families.

“We were literally awash in a sea of scouts,” club member Roger Stevens wrote in ST Report. “We had people lined up eight to ten deep at every station, just waiting to get a chance to try the machines.”

Do you enjoy my retrocomputing histories on Break Into Chat? Please join my email list and stay in touch. 📬

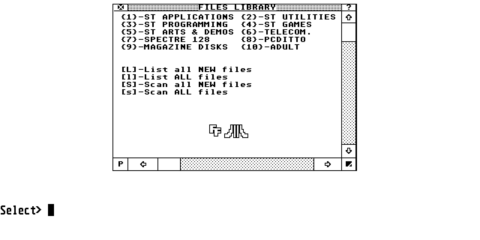

They showed off games, of course, but also desktop publishing, PC and Mac emulators, business software, and even online services.

Many spectators had never heard of the Atari ST, and most were very impressed. It was a big success for ST-JAUG. So of course they returned to Scout World in 1989 with an even bigger booth — almost 40 Atari STs, running games like “Dungeon Master” and “Falcon.”

But promoting Atari to buzzing crowds wasn’t for everyone.

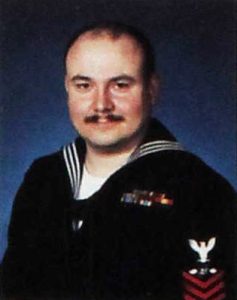

Anthony Rau probably didn’t participate in the Scout World outreach, but he enjoyed ST-JAUG’s other events, like big multiplayer MIDI Maze parties where members would physically link up their computers and play the popular networked first-person shooter game; or more mundane meetings where members would share knowledge and support each other.

Through these get-togethers, Rau got to know many other Atari enthusiasts, including Ralph Mariano and Kevin Moody.

Mariano was one of many sysops among the ST-JAUG ranks who ran a bulletin board system. For Rau it had been a huge help in 1984 to meet fellow sysops like Mariano who could answer his questions and help him as he first set up his own BBS, called “Final Frontier.”

Mariano, who lived just a few miles away, was a major fixture of the Atari scene: he ran the “Bounty BBS,” he published the “ST Report” online magazine, and he sold hard drives through his business, ABCO. Though Mariano was nearly the same age as Rau’s father, he became a friend. Rau even worked for Mariano at ABCO for a while, repairing Atari computers and accessories in his spare time.

This video segment, recorded by Anthony Rau in 1987, shows Ralph Mariano, his computers, and his ABCO workshop. The Atari ST running the “Bounty BBS” can be seen to Mariano’s left, at the 0:13 mark in the video clip.

It was different years later with Moody. He and Rau were close in age and each had served in the Navy. Moody had completed a four-year stint, including time on the USS Mississippi (CGN-40). Rau was on active duty with the VFA-132 squadron, stationed at Naval Air Station Cecil Field.

They were both into BBSing and Rau eventually invited Moody to become a cosysop on “Final Frontier.” You might assume that the two guys running a Star Trek-themed BBS called “Final Frontier” would use handles like “Captain Kirk” and “Mr. Spock,” or maybe “Captain Picard” and “Data.”

Not Rau and Moody. They went by “Frontiersman” and “The Kidd,” respectively.

And, working together, this pair were about to greatly expand the frontiers of Larry Mears’ “Instant Graphics!” protocol.

A SYSOP WHO WANTED TO STAND OUT

In the early days of “Final Frontier,” Rau found he enjoyed spending time crafting menus and art for his board from text using the blocks, arrows, and box-drawing characters available in ATASCII on his 8-bit Atari computer.

Like other 8-bit, 6502-based microcomputers of the late 1970s and early 1980s — such as the Apple II and Commodore 64 — the Atari’s 400, 800, XL, and XE models could display just 40 columns of text on the screen.

Then came the 16-bit revolution in the mid-1980s. Atari debuted its new 520ST in 1985, sporting a Mac-like desktop and powered by the same 68000 processor as the Mac, running at the blazing speed of 8 MHz and boasting half a megabyte of memory. Unlike the monochrome Mac, the new Atari ST machines included two color modes: 16-color low resolution, with 40 columns of text; and 4-color medium resolution, with 80 columns of text.

This was quite an improvement, especially for running a BBS. Rau, Mariano, and many other Atari 8-bit sysops began migrating their boards to ST computers. Rau eventually bought a 1040ST and splurged on a “ridiculously priced” 20-megabyte hard drive — $800 — which would have given him space to host lots of files for download on Final Frontier.

But over time, something felt off to Rau. Though the ST supported higher resolutions than the 8-bit Atari line, its character set lacked most of the semigraphical characters found in ATASCII, making it harder to create attractive textual screens and menus for his BBS.

“The [text] graphics on the Atari ST BBS really sucked for the most part,” Rau told me.

For sysops, differentiation was the name of the game. You needed something unique to attract users to call your BBS — good conversation, better games, a selection of pirated software to download, or just a cool look.

By the late 1980s, Atari sysops faced competition from their IBM PC counterparts whose terminals could display 16 colors and 80 columns of text. In comparison, Rau thought his BBS looked plain.

“We were not trying to make a big splash in the Atari community,” Rau told me. “We simply wanted our BBSes to look as good as, if not better than, the PC BBSes.”

A ‘TIME-CONSUMING PAIN’

It’s not clear exactly how or when Rau and Moody first heard about Larry Mears’ “Instant Graphics!” protocol, but once they did, they were eager to try using it to spiff up Final Frontier with more graphical login screens.

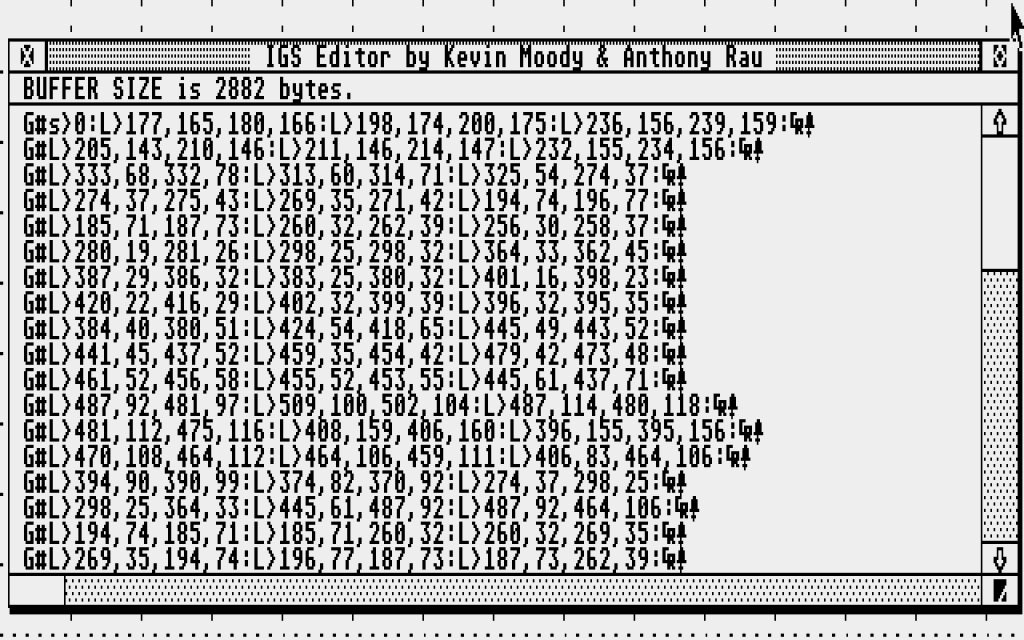

But they found that building IG menus by hand — working out the coordinates and typing the IG commands in a text editor — “was a real time-consuming pain,” Rau told me.

Others might have stopped at these hurdles. But Rau and Moody saw opportunities.

What IG needed, Rau and Moody realized, was a standalone, point-and-click editor. They believed that users would prefer using a visual drawing tool to create art for a visual medium. It would make it easier for people to give IG a try.

So, working from a copy of the IG source code, they began to develop a visual editor for “Instant Graphics!” in C. As they progressed, Ralph Mariano provided them support and the use of his ABCO computer facilities.

Along the way, they also started a second project — developing an IG plugin for the popular Interlink terminal program. This plugin enabled IG to show up as a first-class terminal emulation mode inside Interlink, alongside its built-in VT-52 and ANSI modes. It made for a more seamless and appealing IG user experience.

The creators of Interlink, Intersect Software, were impressed with Rau and Moody’s work, and, according to Rau, congratulated them on being the first to use their software development kit to create such a plugin.

But that wasn’t all. Rau and Moody also added a new feature to IG: sound effects.

To make it happen, they turned to Synthetic Software’s “General Instruments Sound Tool,” or “GIST,” which had a sound driver that could be linked with C projects. They added a b command to the IG protocol, which could play 19 different effects with titles ranging from “Red Alert” to “Helicopter” to “Robot Walk.”

Rau and Moody finished the plugin project first, and released it at some point in early or mid-1989. They called it the “INSTANT GRAPHICS AND SOUND EMULATOR FOR INTERLINK!”

“IG” had become “IGS.”

THE ADVENTURE BEGINS

Larry Mears, the creator of “Instant Graphics!”, soon learned of their work and got in touch. He began making long-distance calls to the Final Frontier BBS in October 1989 to see its new IGS-powered menus. He must have felt proud seeing his protocol in action on someone else’s board. Mears captured these sessions as text files so he could show local Huntsville BBSers examples of what was possible.

Final Frontier’s IGS login screen consisted of a simple illustration of a highway extending to the horizon under a starry sky with the words “THE ADVENTURE BEGINS…” superimposed.

Then, after signing in, a user was treated to a succession of screens, ads, and menus — each transition punctuated with a sound effect. These subsequent screens lacked illustrations or art, but each featured fancy typography over backgrounds, boxes, or borders with different fill patterns and colors.

Larry Mears captured this IGS-powered login sequence of Anthony Rau and Kevin Moody’s “Final Frontier BBS” in September 1989, and distributed it as the file “FIN1.IG” in several releases of “Instant Graphics and Sound”.

Seeing the pair’s achievements — and learning of their other project, the visual editor — energized Mears and inspired him to resume actively developing Instant Graphics.

It also motivated him to reassert his control of the IGS protocol. In late 1989 they made a sort of exchange and a loose federation was born.

Mears would take over the Interlink plugin from Rau and Moody, backporting its new sound effects feature into his original IGS desk accessory after first converting the desk accessory to Laser C. Going forward, he would distribute the desk accessory and Interlink plugin together in one package. For their part, Rau and Moody would continue developing their IGS editor. And as Mears added new features to the IGS protocol, he would provide them with source code so they could support them in the editor.

“Our efforts breathed new life into [Mears’] IGS creation and he began working to improve IGS,” Rau told me. “For a while all three of us were working to make IGS better.”

Indeed, Mears released three new versions of IGS during the fall of 1989, adding significant new features for scaling graphics, bit-blitting parts of the screen, and getting information about the user’s terminal.

Larry Mears included this very rudimentary animation, “S.IG”, with his IG v2.11 release in October 1989.

For these releases, Mears switched to a shareware model. In a lengthy note, he encouraged users to call “Final Frontier” to see what IGS made possible. “You will be absolutely amazed,” he promised. He also begged users to send him any contribution they could afford.

“Most people don’t send anything at all,” he wrote. “So far I’ve made less than $150 on three different projects.”

His efforts did not go unnoticed. Alice Amore highlighted IGS v2.12 in the Nov. 24, 1989, edition of her “Shareware Survey” column in ST*ZMagazine, along with several other programs, saying “It’s a whole new ball game (as far as online graphics are concerned).”

“Here, at last, is a genuine new tool for SysOps and modem potatoes,” she wrote. “It will be interesting to see what the ST community does with the power of INSTANT GRAPHICS in the coming months.”

Her words were prescient — 1990 would prove to be a big year for Instant Graphics.

‘YOU WILL INDEED BE FAMOUS’

After months of labor, Rau and Moody kicked off the new year by uploading the first release of their “IGS Editor Toolbox” to the GEnie online service in January 1990, and they continued updating it throughout the year.

In a recent conversation, Moody took pride in his work programming the editor.

“My IGS editor made it possible for others to create art and sound for the BBS world,” he told me. “I was shocked by some of the artwork I saw.”

Indeed, more and more Atari ST BBSers were dipping their toes in the IGS pond, and when they did, some reached out to Mears, its creator.

“You are a genius, friend,” wrote Ben van Bokkem from Aylesbury, a town in southeast England, in January 1990. “This is the best thing I’ve seen for comms yet. No one here has seen anything like it.”

Van Bokkem was impressed enough that he pitched IGS as a story idea to the UK magazine “ST World.”

A few weeks later, van Bokkem informed Mears that ST World had scheduled a story about IGS for its March issue, and that he was setting up a new private BBS to demonstrate the system to the magazine’s staff. “You will indeed be famous, Larry,” he promised.

There was more. Van Bokkem also mentioned that ST World’s publisher was merging with the Microlink online service — a “big commercial database” like GEnie and CompuServe — and the staff thought IGS would be well-suited for use on the service. “Whatever happens, I shall do my damnedest to make sure you get some financial rewards from your achievements,” he wrote.

It was a tantalizing, if far-fetched, notion for the programmer who had earned so little after spending so many hours of stolen time on three different projects.

Though the dollars never really began to flow, a full-color, double-page spread on Instant Graphics and Sound did appear in the March 1990 issue of ST World, with screenshots of menus from van Bokkem’s new “InterNet BBS.” This story, written by David Stewart, was the biggest publicity yet for Instant Graphics and Sound, and it must have been thrilling for Mears to see his creation in print.

The magazine’s screenshots showed decorative menus but no artwork or illustrations, possibly because InterNet didn’t have any yet. In van Bokkem’s haste to set up InterNet for Stewart to explore, he had had to scrounge around for IGS enhancements to use. It appears he borrowed Rau and Moody’s menu designs from their Final Frontier BBS.

Stewart took a neutral tone in his story, a bit more restrained than Alice Amore.

“The long term popularity of IGS depends upon how accessible the IGS system is made to sysops, and how consistently future upgrades to the software are made,” Stewart wrote. “Watch this space for more information about IGS, if and when it catches on.”

IGS was on the cusp of catching on. In fact, its first auteur was about to emerge, someone who would push the format to its limits.

Up next — Part 4: The artist and the community

Share your thoughts!