This is the first part of a multi-part series.

“My God, what a fantastic program you’ve written! It’s astounding! I’m very, VERY impressed! This will change BBSing in the Atari world forever.”

These words, written in February 1990, kicked off a gushing fan letter — the kind of feedback every hobbyist software developer dreams of receiving.

The writer, Steve Turnbull, was a scenic artist with experience working on television commercials, movies, and music videos. A longtime Atari ST user, Turnbull had just spent a week playing with a telecommunications tool called “Instant Graphics!” The experience compelled him to share his enthusiasm with the program’s creator, Larry Mears.

Amid a (mostly) text-only, pre-Web world, the “Instant Graphics!” protocol — later called “Instant Graphics and Sound,” or IGS — enabled Atari ST bulletin board systems to offer visitors vibrant vector graphics, animations, sound effects, music, and point-and-click mouse interactions.

For Turnbull, playing with IGS had rekindled the lost excitement of telecommunicating, renewing a sense that his computer was alive. He could see new vistas of possibility.

Do you enjoy my retrocomputing histories on Break Into Chat? Please join my email list and stay in touch. 📬

Turnbull’s high praise for IGS must have been water in the desert for Mears, whose work in that space had gone mostly unheralded to that point.

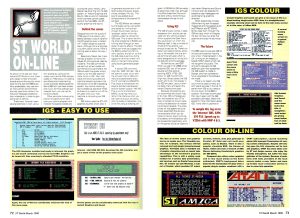

Mears had begun experimenting with these ideas in 1986 with a precursor system called GTerminal, which nobody seems to have used. So he tried again, releasing “Instant Graphics!” in 1988, but the system didn’t really begin to attract attention until 1990, with writeups in the UK’s “ST World” magazine and later in “Atari Interface Magazine.”

With IGS, Mears was among the earliest to succeed in expanding the BBS experience beyond plain text.

Yet, despite its innovations, IGS never achieved wide adoption. It was a niche product, not always easy to use, and it arrived late in the life of the dying Atari ST platform. It was loved by a small circle of people for a while, and then forgotten.

More people, perhaps, remember the Remote Imaging Protocol, or RIP — a graphics language similar to IGS released four years later for the much larger community of PC-compatible BBSes.

Some artists from the ANSI artscene adopted RIP and produced thousands of art pieces throughout the 1990s. Many of these are preserved in archives today like 16colors, while a few modern bulletin boards still carry the torch, notably the late Hawk Hubbard’s “Black Flag BBS,” which offered users an opulent RIP experience.

So even though RIP failed to become the ubiquitous format its creators hoped for — rendered obsolete by the dawn of the World Wide Web — it has a legacy today.

IGS, in contrast, does not. This series aims to right that wrong.

I hope you’ll stick with me, and help spread the word as I publish the next installments looking deeply at IGS, the man who made it, and the people who used it.

And maybe, like me, you may even feel moved to try creating your own IGS art!

About this series

My plan is to publish this history of “Instant Graphics and Sound” in six seven parts over the next several weeks, though this may change:

- Part 1: Introduction

- Part 2: Larry Mears

- Part 3: The Adventure Begins

- Part 4: The Artist and the Community

- Part 5: Point and Click

- Part 6: Legacy

- Part 7: Revival

I have been researching Instant Graphics and Sound since 2019. This series is based on my own correspondence with Larry Mears, Anthony Rau, and Kevin Moody; contemporary private emails, public messages, and artwork captured from GEnie and BBSes by Larry Mears and Tom D’Ambrosio; contemporary documentation and other text files preserved in Discmaster and other archives; articles in publications such as ST*ZMagazine/Z*Net, ST Report, ST World (UK), and Atari Interface Magazine; the personal websites of Larry Mears and Steve Turnbull; and numerous files included in various releases of Instant Graphics, Instant Graphics and Sound, GTerminal, the IGS Editor, Crapz!, Star Battle, and WarLords.

Throughout this series, I have taken the liberty of correcting spelling and minor grammatical mistakes in direct quotes from emails and public messages.

Share your thoughts!