I was introduced to the board game Risk around 1999-2000 by good friends from my college newspaper, The Current. Most were excellent players, each with a favorite strategy and plan of attack.

Though I had never played the board game before, I discovered that I already knew, more or less, how to play. I had learned years earlier by playing a similar game for BBSes called Global War by Joel Bergen.

The differences

Global War was modeled on Risk, but the modem technology employed by BBSes meant that there had to be differences in gameplay.

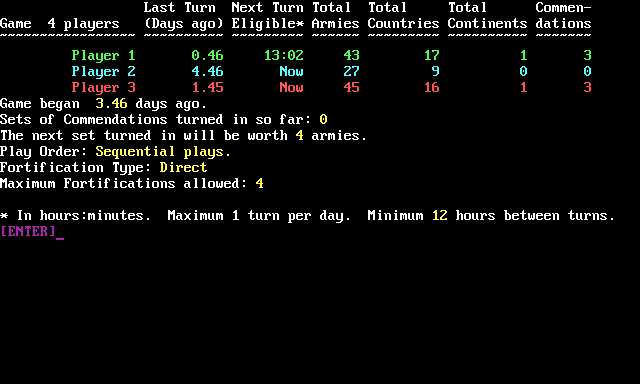

The biggest difference had to do with turns. Most BBSes had only one phone line, so multiple players couldn’t play Global War together in one real-time session as they would the Risk board game. Further, there was no way to be certain when (or if) a user would call in to the BBS on a given day. Global War accommodated this asynchronicity by allowing players to play in any order — but only one turn each per day.

This meant games would last many days; but the actual time a player spent playing was often considerably less than in a Risk game because Global War automated the process of dice-rolling.

The asynchronous gameplay also impacted the social experience. Games of Risk are usually occasions for threats, jokes, whispered offers of alliances. Global War tried to foster this social interaction with a messaging function, but obviously this was inferior to the experience of players being together in one room at one time.

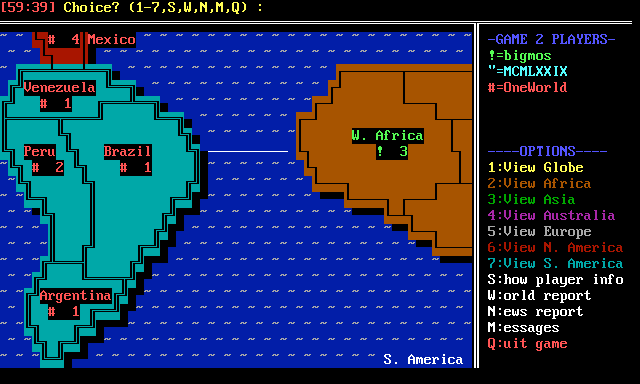

Global War’s maps were rendered using ANSI graphics. They were deliberately simple so that they would load quickly. Bergen went a step further for users with slow modems: he developed a special front-end client for his game called “GWterm” which stored map files on the user’s machine. If a user played via GWterm, the game would only transmit a short code — and GWterm would instantly display the corresponding map.

The biggest gameplay difference I noticed, though, had to do with fortifications. In Risk, standard rules allow players to make one “free move” at the end of their turn where they can take armies from any one territory under their control and move them into an adjacent territory.

In every Global War game I ever played, players chose to use “direct fortification.” This means players can move armies from any one territory in the world to any other territory, so long as they have a string of connected, occupied countries in between.

None of my college friends ever played Risk this way, though it is allowed by the rules. But it was the only way I had ever played!

It’s worth noting that Global War is not the only BBS door game inspired by Risk. The author of the original TradeWars, Chris Sherrick, said he conceived of his game as a cross between a space trading game, the game of RISK, and Hunt the Wumpus. The TradeWars Museum has explored in detail the ways RISK inspired TradeWars’ map structure, turn system, and combat system.

Want to play?

Want to try playing Global War right now? Plenty of BBSes still host the game. Here are a few. You will need a telnet client like SyncTerm.

What do you remember?

Did you ever play Global War? What were your favorite strategies? What made the game memorable to you?

Also, be sure to read my in-depth interview with Joel Bergen, creator of Global War.

Share your thoughts!